The Secrets of Effective Fill Flash Techniques

(by Les Voorhis)

Like

many photographers I spent years looking for ways to improve my

photographs. What was it that made the photos I saw in magazines

and calendars so much better than the images I was making. How

were other photographers able to control the lighting of their

subject so effectively? How can they keep detail in the highlights

and in the shadows?

Like

many photographers I spent years looking for ways to improve my

photographs. What was it that made the photos I saw in magazines

and calendars so much better than the images I was making. How

were other photographers able to control the lighting of their

subject so effectively? How can they keep detail in the highlights

and in the shadows?

As time went by and my skills improved, some things became obvious.

The photographers that I admired used many different techniques

to make their photographs stand out from the rest. Their primary

strength was the time of day that their images were taken. Most

of the stronger images were taken in what photographers call the

"sweet hours" surrounding daybreak and dusk. It is during

this time of the day that the light is of such a quality that

allows images to carry a wide range of tones and still show detail

in shadowed areas as well as the highlight areas. In contrast

were images that were not taken at the "best" time of

day or in the "best" conditions, but the photographers

were able to balance the ambient light to give the image a more

pleasing tonal range. This was accomplished with a variety of

methods, but primarily with the use of fill-flash.

At first, fill-flash seemed a little intimidating. Part of this

is due to the fact that it is impossible to see the results of

the flash until the film has been processed. This, combined with

the difficulty of calculating the correct flash exposure, had

kept fill-flash out of my reach for many years. With the advent

of newer electronic cameras and Through-the-Lens (TTL) flash exposure,

fill flash has been greatly simplified and is now within the grasp

of every photographer. Those willing to do a little experimenting

and learn to "pre-see" how the flash will illuminate

a given subject can greatly increase the control over their images.

Most hot-shoe mounted flash units emit a light roughly daylight

balanced or close to 5500 Kelvin. This is necessary to make them

compatible with the majority of daylight balanced films that nature

photographers use. Also the light generated by this type of flash

unit is of a very short duration. A typical burst lasts 1/1,000

of a second or shorter. Some of the higher powered and more expensive

units can burst as quickly as 1/10,000 or even faster. These quick

bursts can be used very effectively to freeze movement, such as

a hummingbird's wings.

Camera bodies also play a large role in using fill-flash. Cameras

are designed to "synch" with the flash at a particular

shutter speed. These speeds can range from 1/60 of a sec. up to

a 1/250. Any shutter speed slower than this can be used but you

are unable to select anything faster. If we need to use the flash

in bright or sunny conditions we may have to stop the lens down

a smaller aperture to accommodate the slower shutter speeds. In

order to control the amount of Depth of Field and depending on

the subject matter, a smaller aperture may not be a viable alternative.

We need to figure out ways to overcome these shortcomings. One

alternative is to chose a camera body such as Canon's EOS 3 which

when used with a Canon EX series Speedlight you are able to synch

your flash at any shutter speed. Another is to chose a slower

speed film or use a neutral density or polarizing filter over

the lens in order to reduce your effective aperture.

One of the drawbacks to using a flash in the field is the output

strength of the unit itself. The light has a tendency to fall

off very quickly and is unable to span long distances. This is

not a problem for objects that can be photographed close-up such

as flowers or insects, but can be almost useless for large mammals

photographed at distances of 50 - 100 feet or more. The camera's

built in flash typically becomes useless at distances beyond 10

feet so a hot-shoe mounted unit becomes the necessary choice.

A flash extender or Fresnel lens can also be used to increase

this working distance by concentrating the light beam and focusing

it in a much smaller area. These add-ons normally will increase

the flash out put by two to three f/stops. This type of extender

typically must be used with lenses of 300mm in length and longer.

Shorter lenses will cover a larger area than the flash does and

you end up with a portion of your image being spotlit.

Until recently, the main disadvantage to using fill-flash, especially

on mobile subjects, was the difficulty in determining the flash

exposure. Since the flash to subject distance determines the exposure,

using it on anything other than stationary objects was very difficult.

With todays newer TTL cameras, a lot of that exposure determination

is done for us. However, if your camera and flash unit don't allow

for TTL exposure, these same automatic principles apply to any

flash unit that has a thyristor or some sort of built in automatic

meter.

Fill flash is used whenever we want to fill in shadowed areas

of our photographs or whenever we want to balance the tonal range

of the image to within a range that the film can record. Lets

look first at using flash in bright sunlit conditions.

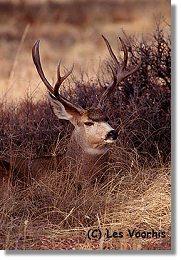

We are photographing a nice mule deer buck that we have been

working with from first light. Three hours later the buck has

now laid down in the shade to escape the hot sun. With fill flash

we can balance the light falling on the buck in the shade with

the background that is lit by the bright sun.

In

this type of situation I typically begin by metering the light

falling on the background. I set my camera body to its fastest

flash sync speed of 1/250th sec. Metering the background gave

me a reading of 1/250 @ f/11 with 100-speed film. I want to open

one stop from that reading in order to keep the background looking

light and natural. I now have an exposure of 1/250 @ f/8. Using

my TTL flash I set the exposure compensation dial to -1/3. I have

found that "dialing the flash down" in this manner,

helps to avoid the "overflashed" in my images. This

is also a great example of how a faster synch speed can be beneficial.

If my camera were to synch at 1/60, my exposure would be 1/60

@ f16, possibly providing more depth of field than I desired in

this situation.

In

this type of situation I typically begin by metering the light

falling on the background. I set my camera body to its fastest

flash sync speed of 1/250th sec. Metering the background gave

me a reading of 1/250 @ f/11 with 100-speed film. I want to open

one stop from that reading in order to keep the background looking

light and natural. I now have an exposure of 1/250 @ f/8. Using

my TTL flash I set the exposure compensation dial to -1/3. I have

found that "dialing the flash down" in this manner,

helps to avoid the "overflashed" in my images. This

is also a great example of how a faster synch speed can be beneficial.

If my camera were to synch at 1/60, my exposure would be 1/60

@ f16, possibly providing more depth of field than I desired in

this situation.

Another excellent time to reap the benefits of fill flash is

when your subject is in very bright, direct overhead light. This

type of light creates a lot of contrast between the highlights

and the shadows. We can use our flash to add detail to those shadowed

areas and more effectively balance our exposure. Since our main

light source is the sun our exposure calculations become easier

than our previous scenario. Setting the camera to its fastest

synch speed (1/250) and using a 50-speed film our exposure is

measured at 1/250 @ f/8. The only thing left to do at this point

is to set the amount of "fill-in" we want from our flash.

My experience has been that adjusting the flash -2/3 to -1 stops

down gives the most pleasing results. You don't want the flash

to be your main source of light, you just want to bring some light

and detail to those heavily shadowed areas. Much more detail has

been gained in the shadowed areas of the snake, opposed to the

image where fill flash was not used.

Using

flash in overcast light can help to bring extra sparkle to your

images as well as add a little more depth. Be very careful not

to overpower the softer ambient light, as all we want is to add

a little spark to the image. Since overcast light can sometimes

carry a blue or "cool" tone our flash unit that is daylight

balanced can actually warm the image a little. You could even

add a slight warming filter to the flash head to warm it up even

more. Theatrical supply companies that sell lighting supplies

can be a great source for flash filters. (TIP: their old sample

packs can even have the exact size gels to fit your flash head

and they sometimes give these away free.)

Using

flash in overcast light can help to bring extra sparkle to your

images as well as add a little more depth. Be very careful not

to overpower the softer ambient light, as all we want is to add

a little spark to the image. Since overcast light can sometimes

carry a blue or "cool" tone our flash unit that is daylight

balanced can actually warm the image a little. You could even

add a slight warming filter to the flash head to warm it up even

more. Theatrical supply companies that sell lighting supplies

can be a great source for flash filters. (TIP: their old sample

packs can even have the exact size gels to fit your flash head

and they sometimes give these away free.)

In this type of light, your shutter speed is much slower than

in the bright sun and it is important to ensure that it is fast

enough to stop your subject's movement. Although the flash can freeze motion, it is not used as a main light and

if you are not careful you can end up with a ghost image. One

exposure comes from the ambient light and can be blurred and a

second more faint but sharper image can come from the lower output

flash. While this can be a creative technique, ensure that this

effect is what you are after.

the flash can freeze motion, it is not used as a main light and

if you are not careful you can end up with a ghost image. One

exposure comes from the ambient light and can be blurred and a

second more faint but sharper image can come from the lower output

flash. While this can be a creative technique, ensure that this

effect is what you are after.

In the image of the mallard drake, the light is low and a 1/30-sec.

exposure @ f/5.6 was required. In low light such as this a direct

on camera flash can also create eye shine. This is the same phenomenon

as "red eye" in humans and can only be eliminated by

moving the flash off of the same axis as the lens. You must use

an off camera synch cord and a bracket. Or you can achieve the

same results by holding the flash off to one side by hand.

I set the flash -1 1/3 below the ambient exposure using the flash

compensation so as not to overpower the image. I will typically

use a much lower amount of fill (more negative compensation) in

overcast situations to avoid overdriving the ambient light.  In

this case it was just enough to add a little highlight to the

water drops on his head and neck and to give him a catch-light

in his eye. I also moved the flash approx. 12 inches off camera

by order to avoid the possibility of eye shine. My experience

has been that any image made in light measuring lower than 1/250

@ f/2.8 (or equivalent exposure) has the possibility for eye shine

so I try to move the flash off the lens axis whenever possible.

How far you move the flash will be determined by how close you

are to you subject as well as how your subject's eyes are positioned

on their head. For example, mountain lions eyes located on the

front of their head will reflect differently than a deer's eyes

whose eyes are located on the side.

In

this case it was just enough to add a little highlight to the

water drops on his head and neck and to give him a catch-light

in his eye. I also moved the flash approx. 12 inches off camera

by order to avoid the possibility of eye shine. My experience

has been that any image made in light measuring lower than 1/250

@ f/2.8 (or equivalent exposure) has the possibility for eye shine

so I try to move the flash off the lens axis whenever possible.

How far you move the flash will be determined by how close you

are to you subject as well as how your subject's eyes are positioned

on their head. For example, mountain lions eyes located on the

front of their head will reflect differently than a deer's eyes

whose eyes are located on the side.

Practice, practice, practice! Experimenting is the best way to

determine which flash settings you prefer and how your particular

setup reacts to each situation. Subjects both lighter and darker

than neutral can also fool the cameras TTL metering system so

bracket your exposures if you can to ensure the best results.

If you feel somewhat overwhelmed by all of this, you are not alone.

Break each of these steps down into pieces and remember the basics

of exposure and light and you can quickly turn your more mundane

images into real showstoppers.

All text and images are copyright Les Voorhis (except where

otherwise noted).

About the Author: Les is a

professional nature/wildlife photographer based in Lakewood, CO.

An avid outdoorsman, Les has photographed our nation's back roads

extensively with heavy concentration in the Rocky Mountain west.

He often heads off the beaten path to areas rarely traveled by

others. His affinity for all things wild and unspoiled has allowed

him to find and capture magnificent images on film. From the wilds

of Alaska to the busy roadways of Rocky Mountain National Park,

he has successfully photographed some of the United States' most

prolific and sometimes elusive wildlife. Elk, Mule Deer, Bald

Eagles, and Mountain Goats are favorite subjects. In the silence

of the predawn hours, he forms a magical unspoken bond with his

subject. That magic is then transferred to film. His exceptional

eye for dramatic light is apparent from his majestic mountain

scenes to his delicately detailed macro work. Les offers photography

seminars in the Denver area. He is actively shooting to add to

his extensive stock photography file. Les' images can be seen

regularly in national and regional publications including Rocky

Mountain Game and Fish and Colorado Outdoors, Bugle Magazine and

American Hunter. A selection of his fine art prints is currently

being showcased in Colorado galleries and gift shops.

You can see more of Les's work at the following

websites:

Profotos

- Les Voorhis

Voorhisphoto.com