The Zone System - Part One

What is the Zone System?

(by Lars Kjellberg)

The zone system was invented by Ansel Adams, one of the most

famous photographers ever. He was a master of technique, and had

an eye for light that few are blessed with. His photographs were

the result of a happy combination of comprehensive technique and

the knack of taking a picture when the light was at its best.

A distinguishing feature of his black and white photographs is

how light and dark areas play off each other in an instantly appealing

manner.

Yet Adams did not approve of what he saw as the 'abuse' of his

zone system. As an old man, he thought far too many people had

misunderstood the method and burdened it with too much mystery.

Why had it turned out like that? Most likely it was poor communication

that was to blame: Ansel Adams was a much better photographer

than he was a teacher. His first books on the zone system are

very hard to follow. The final editions of 'The Negative' and

'The Print' are much better.

The Zone System is Simple

The zone system is very simple and its principles are logical

and easy to understand. Its scientific basis had been known long

before Ansel Adams and Fred Archer hit upon the method in the

1940s. The pioneers were Ferdinand Hurter and Vero Driffield who,

at the end of the nineteenth century, studied the way in which

light sensitive photographic materials reacted during exposure

and development. They succeeded in describing the properties of

light sensitive materials in a graph that showed what was termed

the H&D curve, a curve still in use today in sensitometry.

Art or Science?

Some of the difficulties in understanding the zone system

probably had to do with the conflict between art and science.

Is photography an art or a science? Is it in fact both? If you

decide photography is an art, it becomes difficult for some to

treat it as a science, and thus it inevitably becomes much harder

to grasp what is going on. If, on the other hand, you accept that

photography is both art and science, and understand its principles

on a scientific and logical basis, it becomes much easier. To

my mind this approach does not necessarily intrude upon the artistic

side of photography. On the contrary, a better understanding of

techniques can greatly improve personal creativity. When you really

understand what is happening, you can exploit to the full all

the means photography provides to express your artistic vision.

Visualisation, Exposure and Development

In brief, the zone system is made up of three basic components,

all of which were very important to Ansel Adams: visualisation,

exposure control, and contrast control.

Visualisation is not really a question of technique. It is a method

used to picture the finished photograph before it is taken, and

is useful for everybody, regardless of whether they are using

the zone system or not.

Exposure control is key, partly because it is important to learn

how your own photographic equipment works, and partly because

you want to choose a shutter speed and aperture that will provide

a negative with as much detail as possible. It is with exposure

that we control the reproduction of shadows.

Contrast is controlled by development and the contrast grade

of the paper used for printing. It is the contrast control that

determines how white the picture's light areas will become in

the finished photograph. You should learn to use a suitable development

time that will give you the contrast you are looking for.

Difficult Terms

Visualisation, exposure, and contrast control are terms that

are simple to understand. What can be confusing are the words

Ansel Adams used to describe exposure and contrast control: Zone

V or Zone III exposure, N-2 or N+1 development. However, we will

save these for later and concentrate first on a few basic requirements.

Brightness Levels

It is a common mistake to think that you only take one exposure

each time you press the shutter button. You take an exposure with

a specific aperture and at a specific speed. However, another

thing that affects the exposure is the reflected light from the

object you are photographing, and this can vary greatly for the

same object. The darkest details reflect less light than illuminated

white details. Normally we have a number of different exposures

every time we take a photograph. The object has many different

levels of brightness, sometimes ranging from black in the shade

to white in the sun. The range of exposure values is a result

of variations in both the incident light (sun and shade) and the

ways the object's various surfaces reflect light.

Measuring the range of the contrast in a picture is easy. It

is best to measure the contrast according to the number of exposure

stops from the darkest part of the picture to the lightest. One

exposure stop is the equivalent of a halving or doubling of brightness.

From 1/125 to 1/250 seconds is one exposure stop. From f5.6 to

f8 is also one exposure stop. By first pointing the light meter

at the darkest part of the picture and then the lightest, we can

calculate the number of exposure stops between them. Normally

there are seven stops between shaded black and illuminated white,

but it varies depending on how harsh the incident light is. Direct

sunlight on a clear day will give a very wide range of contrast,

while a grey, hazy day will give a low contrast with few exposure

stops between black and white. Normally, the contrast range varies

between five and nine stops.

Nine stop contrast range, plus all black and all white

Seven stop contrast range, plus all black and all white

Five stop contrast range, plus all black and all white

Film's Exposure Latitude

Photographic film reacts to exposure. When film is developed,

the blackness increases to a large extent in proportion to the

exposure. A strong exposure (a white surface in sunlight) means

that development heavily darkens the negative. A weak exposure

(a black surface in shade) results in little darkening of the

developed negative.

However, film has its limitations. Very weak exposures will not

give any darkening at all, while very strong exposures do not

give any more darkening than slightly weaker exposures would.

The exposure must not be too weak or too strong. We are interested

in the range of exposures that lie between the two extremes of

underexposure and overexposure. We call this range the film's

exposure latitude. A negative black and white film has a wide

exposure latitude of up to fifteen stops. This is much more than

the brightness range of almost all objects we might want to photograph.

A negative black and white film with an exposure latitude of

fifteen stops.

Ideal Exposure

When a film is going to be exposed in a camera, we have to

make sure that all the object's individual exposure values fall

within the film's exposure latitude. If we use too short an exposure

(too small an aperture or too fast a shutter speed) the darkest

areas of the object will end up outside the film's exposure latitude,

and the photograph will be underexposed. If we expose for too

long (too large an aperture or too long a shutter speed) we risk

overexposing the lightest parts of the object, giving flat, bright

areas devoid of contrast.

At a level of two stops underexposure, we will lose the two

darkest stops of the object.

The best results are achieved if we use as short an exposure

as possible without losing any of the shaded details. The way

to do this is to measure the darkest element in the object and

then pick a shutter speed and aperture as close to the threshold

value for underexposure as possible.

The ideal exposure is to place all the tones of the object

except all black, just within the films threshold to the left.

The reasons for choosing short exposures are the numerous advantages

we gain. We have the smallest possible aperture, something that

is generally desirable. We also have a fast shutter speed, which

again works to our advantage. We end up with negatives that are

not overly dark, thus shortening the exposure times when printing

the photographs. Last but not least, the negatives will have a

fine grain (the lighter parts of the negatives being more fine

grained than the darker), which is almost always preferable.

Photographic Paper's Dynamic Range

The point of taking a photograph is to produce a finished

picture on photographic paper. It is the blackening of the paper

that forms the image. In principle, a wide dynamic range produces

the best results. The paper is said to have a wide dynamic range

if it turns fully black in the darkest areas of the image and

is wholly white in the lightest areas, which means that there

is the widest scope for reproducing the image's details. One of

Adams' strengths was that he knew which material to use, and he

always used the best photographic papers.

A very good paper will have a dynamic range corresponding to

more than six exposure stops.

A paper's dynamic range can be measured with a densitometer,

and it can be described in terms of stops of exposure. A very

good paper will have a dynamic range of about six exposure stops.

If you compare this with the object to be photographed, which

normally will have a range of seven stops, you will see that the

paper can therefore reproduce the object's detail with little

or no compromise. If you choose a paper with a range of four stops,

the range of detail will have to be compressed to make it fit

the paper's capabilities. For some photographs this is not much

of a problem, indeed they can even benefit, but if we are looking

for a picture with a full grey scale running from black to white,

paper with a narrow dynamic range will not give particularly good-looking

results.

I want to stress that the point of using the zone system is not

always to produce this kind of photograph. Your aim should be

to learn how to take the kind of picture you want, regardless

of whether you want every last tonal detail, or whether you want

your picture to be soft and grey.

Exposure Controls Shadows

This is an old adage that most people have heard more than

once. What does it mean? Simply put, because it is normal to use

the shortest exposure possible that will still preserve those

details that are in shadow, you should get as close to the threshold

value for underexposure as you can. If you were to go too far,

the detail in the darkest shadows will be lost, and you will end

up with an underexposure. In deciding the exposure, we also decide

how much of the detail in the shadows will be kept. Exposure controls

shadows!

Development Controls Highlights

This is another adage that still holds good. The longer the

development time the higher the contrast, and the greater the

difference between black and white. If you print the photograph

so that the shadows come out right, the highlights will vary with

different development times. A longer time produces lighter highlights

and shorter time produces darker highlights. Development controls

the highlights!

Two Controls

What we have here are two controls, one for the darkest areas

and one for the lightest. Once we have accepted this way of thinking,

things become much easier. An object is made up of different tones

ranging from black to white. To produce pictures with a full tonal

scale you need to know how to control all the tones. To do that,

all you need to do is to adjust the darkest and the lightest parts

of the image. All other tones land between these two extremes,

and will automatically fall into the right places. You control

the darkest tones by learning how your camera and film react to

exposure (by calibrating your equipment) and by then choosing

an exposure that will ensure that the darkest tones will appear

on the negative (by exposing in the correct zone). After this,

you control contrast by picking a development time that ensures

that the lightest areas of the picture will be reproduced on the

photographic paper. The two controls are exposure and development.

It is that simple.

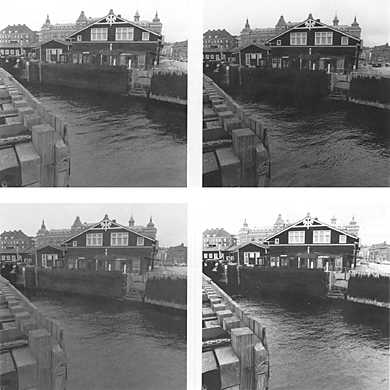

Top left: With correct exposure and correct development,

the image will get a full tonal range from dark tones to bright

highlights.

Top right: With two stops underexposure the result is

an image with lost shadow detail. With a longer exposure and/or

larger apertur opening, the shadows would have been correctly

exposed.

Bottom left: Less development gives lower over-all contrast

and in this case to gray high-lights. With 20% more development

this image would have been better.

Bottom right: Too much development gives to high contrast.

The high-lights are too white without any detail. 30% less development

would have been better.

Next month, we will continue with Part II of the Zone System

- Exposure.

Error processing SSI file

You can see more articles and information

by Lars Kjellberg on the Photodo.com website - a great resource

for photographers around the world!