Eugene

Atget

Eugene

Atget

(1856-1927)

Architecture, Documentary

|

Eugene Atget photographed Paris for thirty years. With a singleness

of purpose rarely excelled, he made his incredible monument to

a city. When he died in 1927 he left approximately 2000 eight

by ten inches glass plates and almost 10,000 prints, not counting

the plates deposited in the Palais Royale archives. Here is one

of the most extraordinary achievements of photography. Yet we

know almost nothing of Atget as a person and less of Atget as

a photographer. His history is to be read in his work.

Eugene Atget Life: Atget was born in Bordeaux in 1856.

An orphan, he was brought up by an uncle. At an early age he shipped

to sea as cabin boy. Doubtless his early experiences made a deep

impression and enriched his vision of the world, for in later

years he vividly recited to friends amusing anecdotes of this

period. Early in his life his faculties of observation were sharpened

and developed.

As a young man, he turned to the stage, first in the French provincial

cities then in the suburbs of Paris. His physique fitted him only

for the less attractive roles usually the villain’s part.

As maturity approached, acting became an unrewarding occupation.

To what should he turn? He had a lively liking for painting and

associated a great deal with painters. He considered being one

of them and indeed tried his hand at painting, a number of examples

of his own brushwork were found at his studio upon his death.

Finally he decided to be a photographer, an art photographer.

He already had an ambition to create a collection of all that

was artistic and picturesque in Paris and its surroundings. An

immense subject. Atget obtained equipment and with a sack full

of plates on his back "started off." Thus began a vast

esthetic documentation, a labor of love for thirty years.

It is necessary to qualify the meaning of "art photographer"

as well as "aesthetic" documentation, since these terms

mean different things to different people. Never was Atget "arty."

His art stems from his grasping of the photographic medium without

confusion or imitation of painting. His vision, backed by heart

and brain, mature sensitivity and above all selectivity was well

synthesized and projected for the beholder to understand and thereby

to be enriched. Maturity, in this case, was not a handicap but

a powerful ingredient.

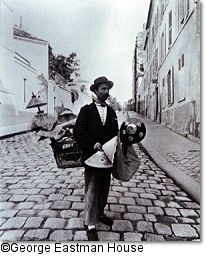

Armed with the experience of travel, observation, and drama,

Atget photographed the monuments of Paris, houses, sites, chateaux,

streets, subjects about to disappear. Photography was no more

materially rewarding than acting. Nevertheless he persevered,

lugging his unwieldy view camera and heavy glass plates. One day

Luc-Olivier-Merson bought a print for fifteen francs. Atget rejoiced

and was encouraged. The playwright Victorien Sardou became interested

in his work and put him on the track of vanishing Paris. Before

the World War of 1914-1918, Atget was gradually winning recognition

and financial support.

But the war broke out "the second that Atget had seen. He

had a horror of it, he loved his work so much." People thought

he was a spy or lunatic. He no longer sold anything when there

was peace again, he was an old man. He produced less and less,

lived, as it were, on his capital of old work. The archives of

the Palais Royale acquired some of his plates, but at low prices

and purely for their record value. So Atget’s life moved

to its close: In 1927 he died, without public recognition or understanding

of the vast importance of his work.

Atget’s Photography: Atget assigned himself an alluring

and provoking subject, the city of Paris, the dream city of thousands

of struggling, aspiring, gifted and would-be poets, painters,

composers. Paris, the city of art and bridges over the Seine,

of boulevards and cafes, of narrow, crooked streets and gray plane

trees in the beautiful Luxembourg gardens.

To Atget, Paris was not a dream but an actuality a fact of hard

material expressions, of strange contrasts and contradictions.

It was weathered, eroded facades of mansion and humble dwelling;

ornate construction of wrought iron grilles and balconies; fantasy

of shop signs and carousels; visible magic of rich grapes, cherries,

cauliflower’s, lobsters, heaped in luxuriance in Les Halles;

formal elegance of Versailles and the Trianon; rustic primitiveness

of a plow lying in furrows outside the fortifications; outmoded

forms of carriage and horse-drawn cabriolet; excitement of an

eclipse seen by crowds in the Place de l’Opera; a thousand

and yet another thousand images of the miracle of daily reality.

In recreating Paris for us and for all time, Atget gave it permanent

reality by utilizing photography in its own right. He did not

veer toward excessive concern with technique nor toward the imitation

of painting but steered a straight course, making the medium speak

for itself in a superb rendering of materials, textures, surfaces,

details. Within the limits of his equipment, he recorded all phases

of the life about him: people, street activity, the city proper.

Atget’s Equipment: The photographs reveal Atget’s

method of work. His equipment consisted of a simple 18 X 24 cm

view camera, with almost none of the present-day adjustments.

It had a rising front, as may be seen by the photographs, many

of whose corners have been cut off because the lens did not give

full coverage. He had no wide-angle lens. The focal length of

his lens is unknown, but it must have been between eleven and

twelve inches. Atget used glass plates. As for accessories, he

certainly did not use an exposure meter. At most he made use of

a simple coefficient table with mathematical calculations. But

it is more likely that he judged exposure by his vast experience

with light conditions, subject matter, and type of plate emulsion.

Because the emulsion used then were non-color-sensitive, he never

used filters. For interior work, he used no artificial light of

any sort but availed himself always of natural light. Any shutter

used with the lens was at most a simple bulb shutter. Atget made

a practice of closing down to a small aperture if conditions permitted.

Only when he photographed people did he open up the diaphragm

and focus critically on the center of interest, leaving the background

out of focus. It is doubtful if his lens could have been faster

than 1/11 at its widest opening. It would seem from the photographs

themselves that most of them were taken during the summer months

when the sun’s actinic rays are stronger. Also most of the

human figures of these series are posed to the extent that Atget

probably asked them "to hold still a moment."

Because he did not have the advantage of fast lenses and fast

emulsions, Atget had to solve his photographic problems within

the capacities of his materials. Since his equipment and materials

were not adequate to stop fast action, he worked a great deal

in the early hours of the day, rising at dawn.

Atget’s photographs are the supreme proof that photography

is more than a "machine." Except for the complex factors

of stopping motion, Atget found no obstacle to making his photographs

an extremely expressive comment on life. Not the camera, but Atget

himself dictated what would be set down in these beautiful prints.

The intensity of his purpose and vision was the powerful drive

which compelled him to undergo long years of neglect and hard

work. At the same time he accepted the tremendous labor of his

method, carrying the cumbersome view camera many miles, weighed

down by bulky glass plates. For him the camera was but an instrument

for expressing his intense awareness of life.

In personal matters Atget was, if not an eccentric was uncompromising.

From the age of 50, he lived solely on milk, bread, and pieces

of sugar. He was absolute in hygiene and in art. This determination

when applied to photography created a unique monument.

More on Eugene Atget:

•George

Eastman House - Eugene Atget Collection

Extensive Gallery of Eugene Aget's Photography